Winning 100 pounds in a 100 year old puzzle contest

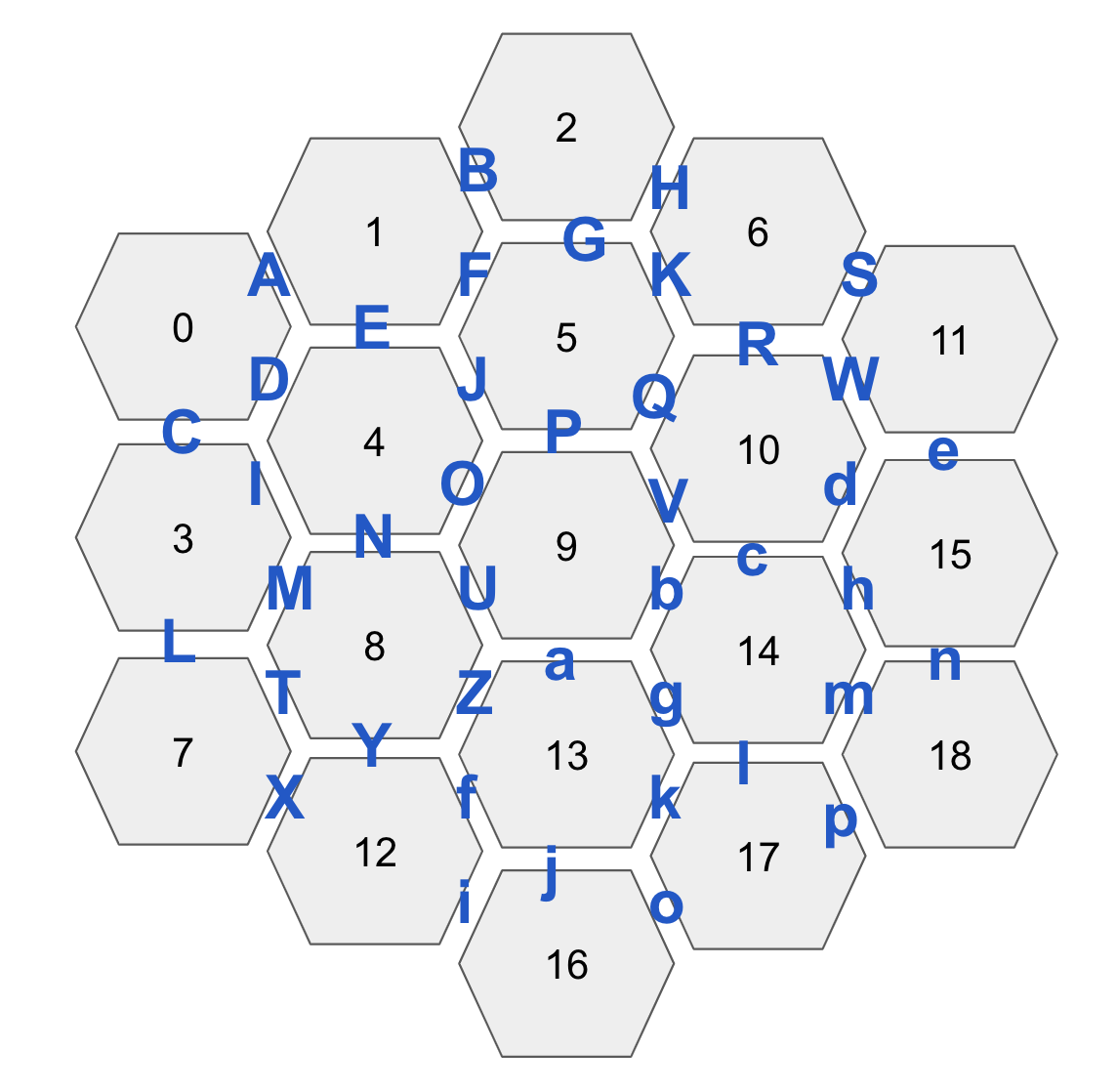

The Daily Mail, a British newspaper still around today, issued a puzzle contest to celebrate their 1 million average daily net sales, which they reached in 1918 and grew to 1,206,408 by the time the puzzle came out in 1920 (which is the reason for that number on the puzzle). They claimed to be “the largest morning sale in the English language and twice the net sale of any American morning newspaper.” [1] The puzzle was to arrange 19 hexagons in the below pattern on the box so that touching sides had the same color. Each hexagon consisted of exactly 6 different colors in some order (there were 2 pairs of identical pieces).

The first person to send in a correct answer received 100 pounds (which is roughly £5600 or $7100 USD in 2024). The next solution different from the first (not just rotation or interchange of duplicate pieces) would receive 100 pounds, and the next after that 50 pounds. It turns out there is only one unique solution (or 24 if you count the trivial transformations of rotating the puzzle or swapping identical pairs), so there was only 1 winner out of the several correct solutions sent in. Solutions had to be submitted by January 3, 1921, so I missed the deadline by a few days.

Since this contest was in 1920, the participants had to work it out by hand. There’s some observations you can apply to reduce the search space that makes manually solving more feasible [2], and people did indeed solve it by hand. Fast forward to 2024, and we now have computers to help us out. I decided to try to solve the puzzle computationally using OR-Tools from Google. Yes, for the purists, this is cheating. But for me, sometimes it’s fun to try to solve a puzzle computationally. And solving puzzles is all about having fun.

I wanted the program to be general enough to solve related problems as well. There is a whole class of pattern matching puzzles out there that can utilize the same approach. I probably could have also solved this problem using BurrTools - it’s meant to solve Burr puzzles, but with some clever ideas, you could turn this into a Burr puzzle. I decided to try a more direct approach to see how I’d fare.

Pattern matching is a class of puzzles where it’s not hard to make the final shape, but it is hard to make sure the rules are satisfied. Tile matching puzzles and Instant Insanity are classic examples of this. It’s easy to create the final shapes (tiles laid out in a square or cubes stacked up), but it’s hard to make sure the rules are satisfied (edges must match or faces on each side of the stack must be different).

Even if you are not familiar with coding, you still might find the below interesting. It shows a way of encoding the puzzle in a way that a computer can understand and solve. This abstraction can encode many different types of pattern matching puzzles.

We define the problem by specifying (1) the pieces and their allowed rotations, (2) the overlapping regions, and (3) the constraints on the overlapping regions.

I will use the above Daily Mail puzzle as an example, but the same process can be used for other types of problems. Once we define these above 3 things, we’re done! We can give that to the solver, and it will hopefully find us a solution! I say hopefully because this class of problems is computationally “hard”, which has a well defined meaning in computer theory. This means the search space might be too large for our puny computers and it might give up or run out of resources before finding a solution. However, since these are small examples, there is a good chance a solution is found. It’s only when we extend these to more pieces that we’d run into issues.

Here is the encoding for the Daily Mail puzzle:

1. Define the pieces and their allowed rotations

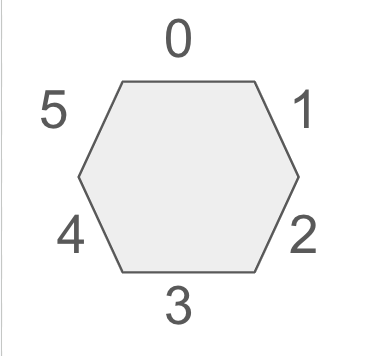

Starting from the top and going clockwise, we will define a piece by listing the colors. For convenience, we’ll always put red at top, but this is not necessary. Then, we will list out all rotations of the piece. We do the same for each of the 19 pieces (tedious but straight-forward. You can write some helper methods that can take some of the tedium out).

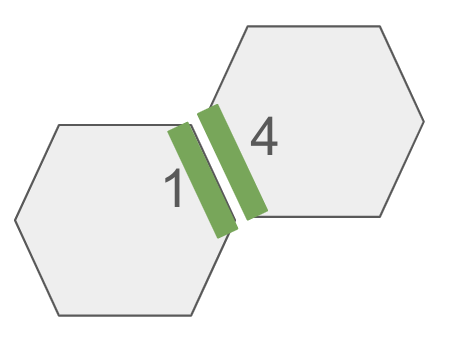

2. Define the Overlapping Regions

We next define regions that are shared by multiple pieces. In this case the region is the border between 2 pieces. There are 42 such regions, and we define these by listing the board locations that share the region, along with the part of the piece that is shared.

3. Define the constraint.

For our example, we want each piece in the shared region to have the same color edge. So our constraint is ALL_SAME. Common constraints are ALL_SAME, ALL_DIFFERENT, Sum == TargetValue, AT MOST ONE

And that’s it! The program knows how to take it from there. The full code can be found here in case you want to play around with it. It took a mere 9 milliseconds to find a solution!

We can translate the results into the actual puzzle configuration and confirm that we did indeed find a solution! This copy of the puzzle probably waited patiently over 100 years to finally be solved.